In new research, planetary scientists from the University of Maryland and elsewhere analyzed melted meteorites that had been floating around in space since the Solar System’s formation around 4.5 billion years ago. They found that these meteorites had extremely low water content — in fact, they were among the driest extraterrestrial materials ever measured. This finding implies that substantial amounts of water could only have been delivered to Earth by means of unmelted, or chondritic, meteorites.

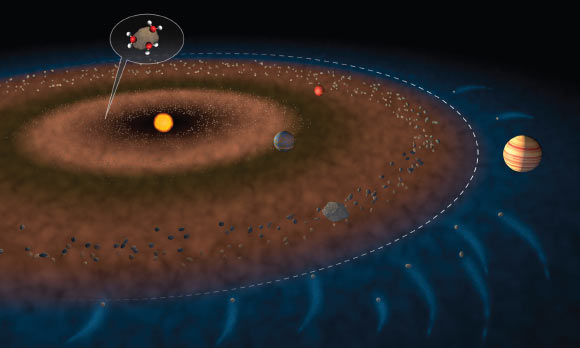

The dashed white line in this illustration shows the boundary between the inner and outer Solar System, with the asteroid belt positioned roughly in between Mars and Jupiter. A bubble near the top of the image shows water molecules attached to a rocky fragment, demonstrating the kind of object that could have carried water to Earth. Image credit: Jack Cook / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“We wanted to understand how our planet managed to get water because it’s not completely obvious,” said University of Maryland researcher Megan Newcombe and colleagues.

“Getting water and having surface oceans on a planet that is small and relatively near the sun is a challenge.”

Dr. Newcombe and co-authors analyzed seven melted, or achondrite, meteorites that crashed into Earth billions of years after splintering from at least five planetesimals — objects that collided to form the planets in our Solar System.

In a process known as melting, many of these planetesimals were heated up by the decay of radioactive elements in the early Solar System’s history, causing them to separate into layers with a crust, mantle and core.

Because these meteorites fell to Earth only recently, this experiment was the first time anyone had ever measured their volatiles.

“The challenge of analyzing water in extremely dry materials is that any terrestrial water on the sample’s surface or inside the measuring instrument can easily be detected, tainting the results,” said Dr. Conel Alexander, a scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science.

To reduce contamination, the researchers first baked their samples in a low-temperature vacuum oven to remove any surface water.

Before the samples could be analyzed in the secondary ion mass spectrometer, the samples had to be dried out once again.

Some of the meteorite samples came from the inner solar system, where Earth is located and where conditions are generally assumed to have been warm and dry. Other rarer samples came from the colder, icier outer reaches of our planetary system.

While it was generally thought that water came to Earth from the outer Solar System, it has yet to be determined what types of objects could have carried that water across the Solar System.

“We knew that plenty of outer solar system objects were differentiated, but it was sort of implicitly assumed that because they were from the outer solar system, they must also contain a lot of water,” said Dr. Sune Nielsen, a researcher at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“Our paper shows this is definitely not the case. As soon as meteorites melt, there is no remaining water.”

After analyzing the achondrite meteorite samples, the scientists discovered that water comprised less than two millionths of their mass.

For comparison, the wettest meteorites — a group called carbonaceous chondrites — contain up to about 20% of water by weight, or 100,000 times more than the meteorite samples studied by the team.

This means that the heating and melting of planetesimals leads to near-total water loss, regardless of where these planetesimals originated in the solar system and how much water they started out with.

The study authors discovered that, contrary to popular belief, not all outer Solar System objects are rich in water.

This led them to conclude that water was likely delivered to Earth via unmelted, or chondritic, meteorites.

“Water is considered to be an ingredient for life to be able to flourish, so as we’re looking out into the Universe and finding all of these exoplanets, we’re starting to work out which of those planetary systems could be potential hosts for life,” Dr. Newcombe said.

“In order to be able to understand these other solar systems, we want to understand our own.”

The study was published in the journal Nature.

_____

M.E. Newcombe et al. Degassing of early-formed planetesimals restricted water delivery to Earth. Nature, published online March 15, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05721-5