Saturn’s ring system may well have formed when dinosaurs were still walking on the Earth, and will last only another few hundred million years at most, according to two new studies published in the journal Icarus.

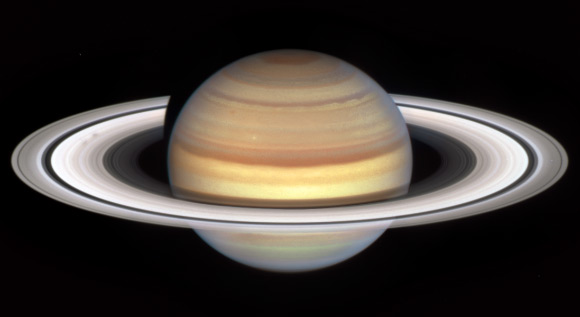

This Hubble image heralds the start of Saturn’s ‘spoke season’ with the appearance of two smudgy spokes in the B ring, on the left in the image. Image credit: NASA / ESA / Amy Simon, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center / Alyssa Pagan, STScI.

All of the giant planets of the Solar System have ring systems, the majority of which are relatively low mass and composed of ringlets, arcs or gossamer rings and whose characteristics indicate that they are spectrally dark and that water ice is essentially absent or not a dominant compositional constituent.

This is in stark contrast to the Saturnian rings which are relatively massive and composed of % water ice by mass.

That Saturn’s rings are so massive and icy is almost certainly a clue to their origin and age.

“Our inescapable conclusion is that Saturn’s rings must be relatively young by astronomical standards, just a few hundred million years old,” said Indiana University Professor Emeritus of Astronomy Richard Durisen.

“If you look at Saturn’s satellite system, there are other hints that something dramatic happened there in the last few hundred million years.”

Professor Durisen and his colleague, Dr. Paul Estrada of NASA’s Ames Research Center, have long argued that Saturn’s rings are relatively young.

However, it wasn’t until data was available from NASA’s Cassini mission — particularly its 2017 Grand Finale, consisting of 22 orbits passing between Saturn and its rings — that they were able to use theoretical models to determine the age and longevity of the rings with confidence by computing how the rings change over long periods of time.

Particularly important for their work were Cassini’s measurements of the meteoroid influx rate, the mass of the rings and the inflow rate of ring material onto Saturn.

The impact of meteoroids not only pollutes the rings, it ultimately leads to ring material drifting inward toward the planet.

The theoretical models presented by the authors demonstrate that the rings should be losing mass onto the planet at the prodigious rate of many tons per second that Cassini observed, which means that the remaining lifetime of the rings is only another few hundred million years or so.

For the first time, their detailed computations combine viscous spreading — due to ring particle interactions — with meteoroid effects in simulations designed to span the full lifetime of a ring system like Saturn’s.

They demonstrate that meteoroid impacts are what ultimately impose a short lifetime compared with the age of the Solar System, given the meteoroid influx rate measured by Cassini.

“We have shown that massive rings like Saturn’s do not last long,” Dr. Estrada said.

“One can speculate that the relatively puny rings around the other ice and gas giants in our Solar System are left-over remnants of rings that were once massive like Saturn’s.”

“Maybe some time in the not-so-distant future, astronomically speaking, after Saturn’s rings are ground down, they will look more like the sparse rings of Uranus.”

_____

Richard H. Durisen & Paul R. Estrada. 2023. Large mass inflow rates in Saturn’s rings due to ballistic transport and mass loading. Icarus 400: 115221; doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115221

Paul R. Estrada & Richard H. Durisen. 2023. Constraints on the initial mass, age and lifetime of Saturn’s rings from viscous evolutions that include pollution and transport due to micrometeoroid bombardment. Icarus 400: 115296; doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115296