Earth’s Moon shrank more than 46 m (150 feet) in circumference as its core gradually cooled over the last few hundred million years, according to a paper published in the Planetary Science Journal. In much the same way a grape wrinkles when it shrinks down to a raisin, the Moon also develops creases as it shrinks. But unlike the flexible skin on a grape, the lunar surface is brittle, causing faults to form where sections of crust push against one another.

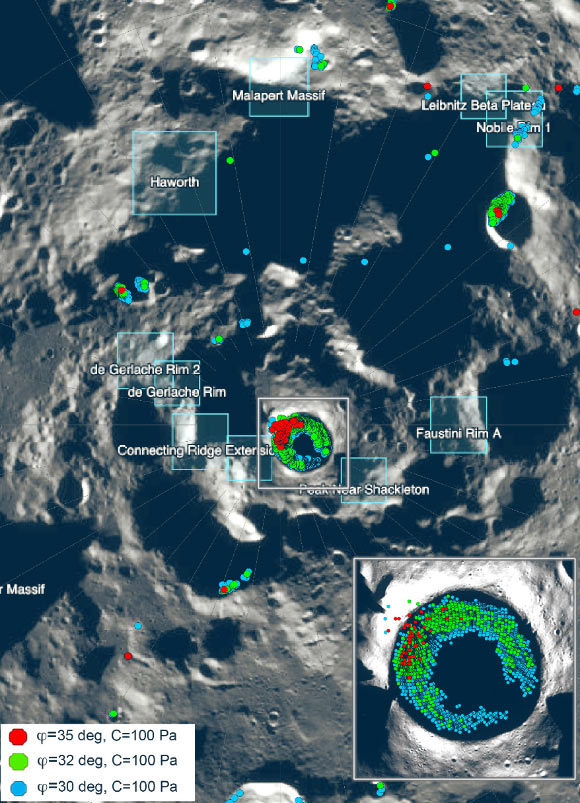

Predicted areas of slope instability in the south polar region of the Moon; the image is centered on Shackleton crater; locations of proposed Artemis III landing regions are shown (blue boxes); the model predicts that large portions of the interior walls of Shackleton crater are susceptible to landslides (inset), as are portions of the interior crater walls in the Nobile Rim 1 region. Image credit: Watters et al., doi: 10.3847/PSJ/ad1332.

“Our modeling suggests that shallow moonquakes capable of producing strong ground shaking in the south polar region are possible from slip events on existing faults or the formation of new thrust faults,” said Dr. Tom Watters, a planetary researcher at the Smithsonian Institution.

“The global distribution of young thrust faults, their potential to be active, and the potential to form new thrust faults from ongoing global contraction should be considered when planning the location and stability of permanent outposts on the Moon.”

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera onboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has detected thousands of relatively small, young thrust faults widely distributed in the lunar crust.

The scarps are cliff-like landforms that resemble small stair-steps on the lunar surface.

They form where contractional forces break the crust and push or thrust it on one side of the fault up and over the other side.

The contraction is caused by cooling of the Moon’s still-hot interior and tidal forces exerted by Earth, resulting in global shrinking.

The formation of the faults is accompanied by seismic activity in the form of shallow-depth moonquakes.

Such shallow moonquakes were recorded by the Apollo Passive Seismic Network, a series of seismometers deployed by the Apollo astronauts.

The strongest recorded shallow moonquake had an epicenter in the south-polar region.

One young thrust-fault scarp, located within the de Gerlache Rim 2, an Artemis III candidate landing region, is modeled in the study and shows that the formation of this fault scarp could have been associated with a moonquake of the recorded magnitude.

In their study, Dr. Watters and colleagues also modeled the stability of surface slopes in the lunar south polar region and found that some areas are susceptible to regolith landslides from even light seismic shaking, including areas in some permanently shadowed regions.

These areas are of interest due to the resources that might be found there, such as ice.

“Shallow moonquakes can devastate hypothetical human settlements on the Moon,” said Dr. Nicholas Schmerr, a researcher at the University of Maryland.

“You can think of the lunar surface as being dry, grounded gravel and dust. Over billions of years, the surface has been hit by asteroids and comets, with the resulting angular fragments constantly getting ejected from the impacts.”

“As a result, the reworked surface material can be micron-sized to boulder-sized, but all very loosely consolidated. Loose sediments make it very possible for shaking and landslides to occur.”

“To better understand the seismic hazard posed to future human activities on the Moon, we need new seismic data, not just at the South Pole, but globally,” said Dr. Renee Weber, a researcher at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.

“Missions like the upcoming Farside Seismic Suite will expand upon measurements made during Apollo and add to our knowledge of global seismicity.”

“LRO is committed to acquiring data of the lunar surface to aid scientists in understanding important features such as thrust faults,” said LRO deputy project scientist Dr. Maria Banks, a researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“This study is a good demonstration of one of the many ways in which LRO data is being used to assist planning for our return to the Moon.”

“As we get closer to the crewed Artemis mission’s launch date, it’s important to keep our astronauts, our equipment and infrastructure as safe as possible,” Dr. Schmerr said.

“This work is helping us prepare for what awaits us on the Moon — whether that’s engineering structures that can better withstand lunar seismic activity or protecting people from really dangerous zones.”

_____

T.R. Watters et al. 2024. Tectonics and Seismicity of the Lunar South Polar Region. Planet. Sci. J 5, 22; doi: 10.3847/PSJ/ad1332