New research from the University of Bristol sheds light on the origin of titanium-rich basaltic magmas on the Moon.

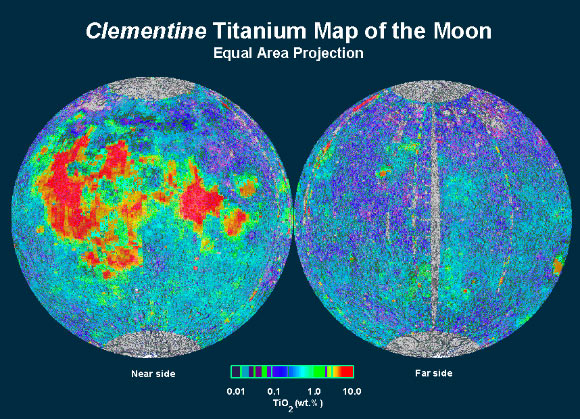

A map of the titanium abundances of the Moon’s surface, obtained from NASA’s Clementine spacecraft; the red parts indicate extremely high concentrations compared to terrestrial rocks. Image credit: Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Surprisingly high concentrations of the element titanium (Ti) in parts of the lunar surface have been known since NASA’s Apollo missions, back in the 1960s and 1970s, which successfully returned solidified, ancient lava samples from the Moon’s crust.

More recent mapping by orbiting satellite shows these magmas, known as high-Ti basalts, to be widespread on the Moon.

In a series of high temperature lab experiments with molten rocks and sophisticated isotopic analyses of lunar samples, University of Bristol’s Professor Tim Elliott and his colleagues identified a critical reaction that controls the composition of these distinctive magmas.

This reaction took place in the deep lunar interior some 3.5 billion years ago, involving exchange of the element iron in the magma with the element magnesium in the surrounding rocks, modifying the chemical and physical properties of the melt.

“The origin of volcanic lunar rocks is a fascinating tale involving an ‘avalanche’ of an unstable, planetary-scale crystal pile created by the cooling of a primordial magma ocean,” Professor Elliott said.

“Central to constraining this epic history is the presence of a magma type unique to the Moon, but explaining how such magmas could even have got to the surface, to be sampled by space missions, has been a troublesome problem. It is great to have resolved this dilemma.”

“Until now models have been unable to recreate magma compositions that match essential chemical and physical characteristics of the high-Ti basalts,” said Dr. Martijn Klaver, a researcher in the Institute of Mineralogy at the University of Münster.

“It has proven particularly hard to explain their low density, which allowed them to be erupted some three and a half billion years ago.”

“We managed to mimic the high-Ti basalts in the process in the lab using high-temperature experiments,” the researchers said.

“Measurements of the high-Ti basalts also revealed a distinctive isotopic composition that provides a fingerprint of the reactions reproduced by the experiments.”

“Both results clearly demonstrate how the melt-solid reaction is integral in understanding the formation of these unique magmas.”

The findings appear today in the journal Nature Geoscience.

_____

M. Klaver et al. Titanium-rich basaltic melts on the Moon modulated by reactive flow processes. Nat. Geosci, published online January 15, 2024; doi: 10.1038/s41561-023-01362-5