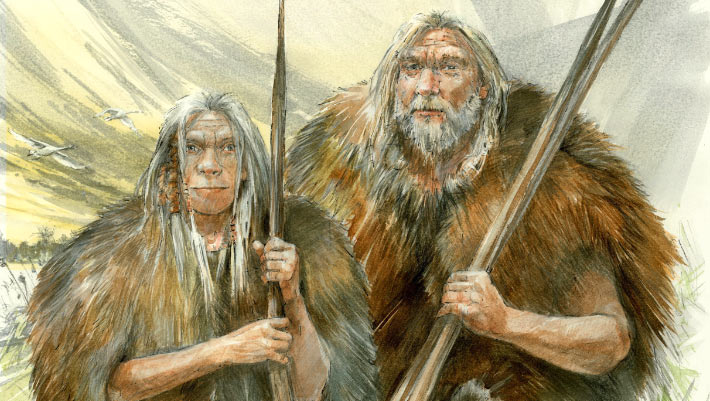

Researchers from the University of Tübingen and elsewhere have unearthed the cutmarked bones of cave bears at the Middle Pleistocene site of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Bear skins have high insulating properties and might have played a role in the adaptations of Middle Pleistocene hominins, such as Homo heidelbergensis depicted here, to the cold and harsh winter conditions of Northwestern Europe. Image credit: Benoît Clarys.

“Cut marks on bones are often interpreted in archaeology as an indication of the utilization of meat,” said lead author Dr. Ivo Verheijen, a researcher with the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment at the University of Tübingen and the Forschungsmuseum Schöningen.

“But there is hardly any meat to be recovered from hand and foot bones. In this case, we can attribute such fine and precise cut marks to the careful stripping of the skin.”

“A bear’s winter coat consists of both long outer hairs that form an airy protective layer and short, dense hairs that provide particularly good insulation. Bears, including extinct cave bears, needed a highly insulating coat for hibernation.”

In their study, Dr. Verheijen and colleagues examined the 320,000-year-old bear bones from the Schöningen site in Germany.

The very thin cut marks found on the specimens indicate delicate butchering and show similarities in butchery patterns to bears from other Paleolithic sites.

Detail of the precise and fine cut marks on the metatarsal of a cave bear from the Middle Pleistocene site of Schöningen in Germany. Image credit: Volker Minkus.

“These newly discovered cut marks are an indication that about 300,000 years ago, people in northern Europe were able to survive in winter thanks in part to warm bear skins,” Dr. Verheijen said.

“But how were the bear skins obtained? Schöningen plays a crucial role in the discussion about the origin of hunting, because the world’s oldest spears were discovered here.”

“Did the people of that time also hunt bears? There are some indications for this.”

“If only adult animals are found at an archaeological site, this is usually considered an indication of hunting — at Schöningen, all the bear bones and teeth belonged to adult individuals.”

“In addition, bear skin must be removed shortly after the animal’s death, otherwise the hair is lost and the skin becomes unusable.”

“Since the animal was skinned, it couldn’t have been dead for long at that point.”

“The find opens up a new perspective,” said senior author Professor Nicholas Conard, a researcher with the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, the Institute for Archaeological Sciences, and the Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology at the University of Tübingen.

“The location of the cut marks indicates that the cave bears were also exploited for their skins.”

“So animals were not only used for food, but their pelts were also essential for survival in the cold.”

“The use of bear skins is likely a key adaptation of early humans to the climate in the north.”

A paper describing the findings was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

_____

Ivo Verheijen et al. Early evidence for bear exploitation during MIS 9 from the site of Schöningen 12 (Germany). Journal of Human Evolution, published online December 23, 2022; doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2022.103294